There are two basic gears in Planet of the Apes: adventure and allegory, and it’s stuck fast in both from start to finish. First, its bullet-straight story rarely lets up. Charlton Heston makes sure of that – if the story slows to take a breather, it’s doing it by giving him a paragraph to chew on with those great, headstone teeth of his. The way he grinds through dialogue with his growling staccato is tantamount to a chase scene you can’t look away from. Second, it’s a fit for any reading you want to give it re: human-on-human oppression. Its running time is especially jammed with allusions to the racial tension that was raging across the country upon its release – the same tension that makes the movie relevant still. The first Apes film is an unmistakable parable of America’s racial divide and the persistent social death it metes out, but looking ahead at the sequels that followed, it’s clear producer Arthur P. Jacobs intentionally drew that material ever closer to the top. The last two sequels especially (Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and Battle for the Planet of the Apes) jump headfirst into the fray, moving the series from a mode of mere commentary to outright rallying cry. But equally effective is the movie’s strong punch of religious satire, illustrating how a very human strain of oppressive fundamentalism was inherited into this future ape society completely intact and undimmed by time, wielded to maintain order among the castes and as a progress-bludgeoning dismissal of the possibility of human agency of any kind. The repression of knowledge to maintain this status quo is manifested as a society of apes that can never advance beyond the most rudimentary dwellings or the most primitive, nearly medieval of governmental systems. Yet with all this meaning packed into the narrative, it’s still wall-to-wall fun. The movie is simply one of those titanic science fiction achievements that can stand as a litmus for all stripes of discontent without sacrificing so much as a picked nit of its entertainment value.

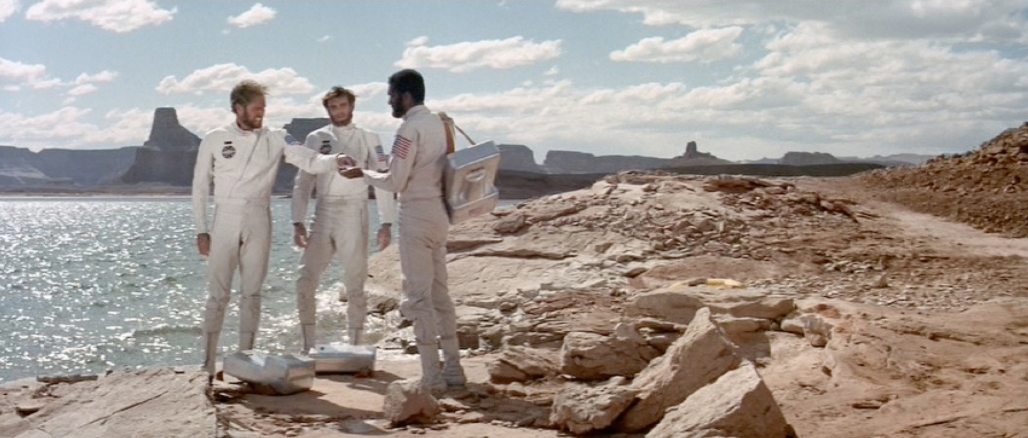

Adapted from Pierre Boulle’s novel, but excised of its future/modern settings in favor of more Fox Ranch-friendly clay huts and bridges, the story’s infused with the sardonic totems of formerly blacklisted writer Michael Wilson’s hard-won perspective – namely a voice-deprived man surrounded by aggressive, narrow-minded accusers in a mock trial – and is sprinkled on top with the most Twilight Zoney of twist endings by, of course, the primogenitor of such elegance, Rod Serling. By closing credits, the movie’s (and much more so the series’) vicious narrative loop becomes the ultimate extrapolation of the old adage “wherever you go, there you are.” Astronaut Taylor (Heston) and his crewmates, including one en-route fatality, crash land on a planet they believe to be in the constellation Orion. Their ship doomed to the alien sea, the three survivors face the harsh, open wilderness, surviving on thin supplies, but nearly succumbing to Taylor’s withering adjudication of their hollow motives for even volunteering for such a mission. “You got what you wanted, Tiger. How does it taste?” Counter to the typical hero’s journey, wherein the goodness of a character’s stock is challenged, here the story is a grinder through which Taylor’s black humor and superiority are tested and found to be particularly suited to the bleak truths he’s about to face.

Heston’s Taylor is the brawny stand-in for the fed-up, disaffected, late ’60s urbanite: dismissive of intimations of glory (just shy of name-dropping Ozymandius), suspicious of prestige posturing, and openly, laughingly contemptuous of patriotism. He’s the cynic as spaceman, and he never seems so much nonplussed by his stranded circumstance as in a mode of thankful anticipation for some perfect new life awaiting him just beyond the tree line. But soon come the apes on horses – still a gut-punching image – sweeping through the fields, purging it of its human vermin. Throat-shot Taylor (and his even less-lucky brethren) gets taken to Ape City, where his bright eyes help graduate him to favorite specimen for some dutiful chimpanzees – Cornelius the skeptical (Roddy McDowall) and Zira the overly-doting (Kim Hunter). It’s fun to watch Zira fall in love with Taylor over the course of the movie – witness her melting expression when she finds he can write his own name, see her lunge protectively as he’s manhandled by some rough gorillas, hear her fuss jealously over Taylor’s ad-hoc wife, Nova: at the escape site, it’s not “Why did you bring the other one?!” but “I told you not to bring the other one!” And when Taylor wants to give her a kiss goodbye, methinks the ape doth protest too much.

Cornelius and Zira are the earnest-meets-snarky soul of the movie, so indelible and popular they got their own sequel (Escape from the Planet of the Apes), the charming glibness of which plays at times like a TV show spinoff from a movie – until it gets as damning and bleak as its predecessors by the final sequences. Here, they mostly stand as the only shield between Taylor’s protestations and sure death by the House Un-Apish Activities Committee, led by the sanctimonious head of science and religion, Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans). From there it’s an escape, a chase, an iconic epithet that denigrates apes everywhere, not just the damn dirty ones, and another escape before we get to the final showdown at the cave of enlightenment. There, Taylor shaves himself down into Richard D. Zanuck before positing a world where man was there before the ape, and did this cockeyed world better. Moments later, when Cornelius is reading the 29th scroll aloud – essentially a Bible-y rewrite of Taylor’s own angry cynicism at the beginning of the movie – there’s a look on Taylor’s face, torn between flinty outrage and shamed agreement with the apes’ assessment of man’s disposable value, as if he might just side with the apes for once, but might just as easily launch into a defense of his own kind. Armed with this ambivalence – and an ape-fashioned M1 carbine – he at last rides into the sunset, Nova in tow, to find his destiny…and finds it in a pointy metaphor half-buried in the surf. It’s this man’s greatest humbling to find out the world he’s run away from for its myopic self-corruption, but which has become over the span of an ape-oppressive adventure a place he might like to call home again, has actually lived out all its worst self-destructive impulses and then some. Taylor’s surf-pounding profanities at the bitter-black conclusion of the story are the ineffectual condemnations lobbed up to a species already dead-and-gone, empty rejoinders to the ultimate act of destruction rising up unheard into the radioactive ether. It’s a pitch-dark ending challenged in its bleakness only by the ending of its own sequel (the Earth-destroying Beneath the Planet of the Apes).

The movie’s scope, defined by its intergalactic, centuries-crossing canvas, is illuminated and enhanced by director Franklin Schaffner’s sure wide-screen storytelling. While filling the frame with visceral action, there’s also attention given to the relative sparseness of the world, the near-agoraphobic vulnerability inherent in a tiny ape community from which the empty world extends away forever in every direction and in every variation from desert to sea. There’s an aloneness inherent in the setup, and an anxiety layered in as one sees, from a sardonic god’s-eye view, the numerically insignificant population of this hirsute township organizing itself under the rule of an ape law that requires rigid separation and fanatical obedience to a law set down a millennium before by a mythical-sounding “lawgiver”. Ape City is any subgroup so frightened by its own exposure that it holes up in a word-fort constructed and christened by their vaunted heroes of legalism. It’s fun to think of this Zaius-enforced rule-mongering against Schaffner’s next film,Patton (1970). In their respective films, Zaius and Patton share the mantle of leadership as enforced by their cartoonishly dogmatic adherence to the book of regulations. But whereas Zaius exists in a world of wonky but pure sci-fi satire, where even one with heavy things on its mind can be easily seen for the darkly twisted comedy that it really is, Patton resides in a much more automatically respectable dramatic bio-pic where the nose-thumbing goes on so deep beneath the thick folds of an Army-issued sheepskin B-3, that it’s arguably not there at all. Zaius, as played by Evans, at least displays a modicum of “human”ism – maybe it’s just the charm innate in the old Shakespearean – so that the reasons for his strict dogma come eking through as something less than unmitigated villainy: once we see that final image on the shore, and we know what became of man, and how they “finally really did it”, we can ping back to Zaius’s dug-in heels and think, well, maybe he’s not so wrong being such a buzzkill after all.

On paper, the movie is essentially a big, silly concept that does everything so right, from the writing to the casting to the music and makeup, that it registers on screen with an air of earned legitimacy. Jerry Goldsmith’s one-of-a-kind score keeps us unsettled and tense across the first half hour’s long wilderness trek, and then leaves us gripped throughout by an otherworldly ambiance up to the near-soundless closing moments of shocked discovery. John Chambers’ inventive makeup effects won him an honorary Oscar, a fact made more astounding in the year of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Stuart Freeborn and Daniel Richter’s more detailed, realistic man-ape work on that film was all but overlooked – perhaps cementing the gap between heady tone poems and outright entertainment, as far as Hollywood is concerned.

But in more ways than mere accolades, Planet of the Apes will always be the dark flip side of 2001‘s forward-leaning hope for the upward evolutionary leap of mankind. 2001 pulls us into a cosmic mystery that leads to a greater, if still opaque, optimism, whereas Apes can only revel in audience indictment over the truth of an inborn aggression that can never be sated except by global obliteration. And true to this fascination for self-annihilation, the audience kept coming back for more and more – through five movies, the overarching message of which is: no act of kindness or sacrifice can ever jump us out of this endless loop of destruction and despair. It’s a sentiment that cannot be matched by the current iterations’ relatively less philosophically-rooted storytelling, despite current history’s ever-renewable justification for it. And for this reason, it may be that the original and superior Planet of the Apes will never be bested as perhaps the most entertaining downer in movie history.